Jean Pechaud.

1852-1861

© Bibliotheque Nationale through Annick Foucrier

Jean Pechaud was born Octaber 31, 1823, in Chavagnac, France, the sixth of ten children of Joseph and Marguerite Pechaud. His father was a miller but also worked as a watchmaker, farmer, and even as a veterinarian, to put food on the table for his large family. His mother died after the last child was born and his father then married the family servant girl. Once mistress of the house, the latter turned into the proverbial harridan of a stepmother, and Jean, at the age of fourteen, found himself on the doorstep.

The youth was taken in by a wandering tinker who kept him for one season and then sent him on his way again with ten ecus for his efforts. With this newfound fortune, he became an umbrella salesman and went from village to village peddling his wares. Finally, in 1840, Jean became a clerk in a fabric store in the town of Chateau-Thierry. He was given to think that he would inherit the shop but the owner surprised him and left it to a nephew instead. Jean found a new position and sent for his younger brother Francois. All seemed to be going well until the Revolution of 1848. The business where he was employed was among the many that went under.

News of the Gold Rush was like salve for the wounds and so the Pechaud brothers left France from Le Havre on the Espadon, a whaling ship, on October 20, 1849. After five months and nineteen days at sea, they arrived in San Francisco. Years later, Jean would write down his adventures all too briefly for our modern thirst for understanding of those Gold Rush years, and unfortunately with the astigmatism of old age that blurs one's surroundings and alters time. Nevertheless, in spite of gentle lapses of memory and the fiction of distance, the grain of truth is there for us to see. He continues now in his own words:

"When my brother and I landed at San Francisco, we were practically penniless in the midst of an unknown city where all around us people were speaking in unrecognizable languages. We felt rather stupid and ill at ease, and we spent our first night stretched out on boards in an open courtyard, paying 15. francs for the privilege.(There were five francs to the dollar at that time.) We realized' that at these prices, we could not stay idle. For lack of anything better, we became porters. Per day we sometimes earned 60, 70, even 100 francs, and in spite of these seemmgly large sums of money, everything was so frightfully expensive, that by the evening little remained in our pockets."

"After some time in this backbreaking endeavor, we let ourselves be taken in by the promises of an entrepreneur who led us three days distant from the city to his property where there was not even a hut to shelter us. We were forced to live like savages, and even worse, we fell ill. But thanks to our strong constitutions, we were able to recover our strength.

"While we were in San Francisco, I had noticed the lack of fodder for animals, and an idea came to me. I paid 80 francs for a scythe, and with another that had been loaned to us, my brother and I began to cut hay which we carried on our backs, for want of any other transportation. In two weeks we had earned a tidy sum with which we purchased a brace of oxen and a cart. Each trip made, made us about 150 francs. All the hay cost us was the effort to cut it out in the countryside. Our business was going so well that others began to imitate our efforts, and competition eventually forced us out of business. We were going to begin anew in San Jose, a small town that was at the time the capital of the state, when an epidemic broke out there and decimated the population, forcing us to look elsewhere. (Undoubtedly this was one of the many outbreaks of cholera.)

"We then set out for the mines. After a long trip mto deep gorges and over mountains, through swampy prairies and barely penetrable woods we arrived at Stockton, a newly-founded city on the San Joaquin River.

"Unfortunately for us, we met a company of forty mmers who were headmg for Murphy's Diggins and we let ourselves be talked into joining them. Everything went wrong. After a thousand fruitless attempts, we left their company, and in order to earn our daily bread, we became farmers, drivers, wood merchants, and even building contractors. We even constructed an oven for a baker named Charrette who, by the strangest of coincidences, was a photographer when I met him again in 1869, in Algeria when I was visiting the town of Blidah. '

"From Murphy's, we set out for Columbia. There we built a forge and a small house."

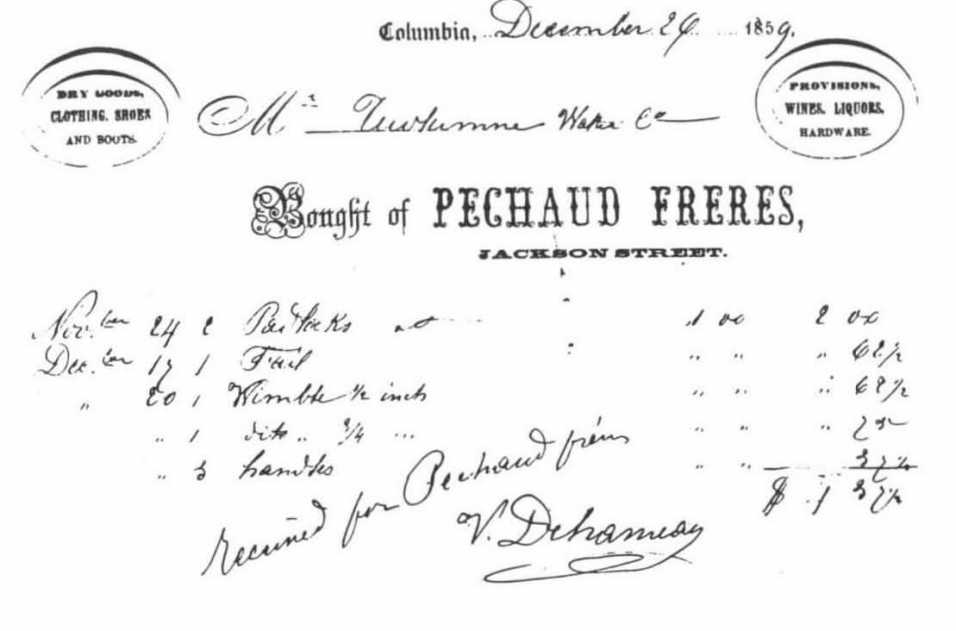

1852 - Pechaud's first appear on the property tax rolls. (Barbara Eastman,)

1852 - Pechaud's owned one lot with improvements, located west of Samuel Dealy's and Jacob Smith's Meat Market, between Main and Broadway streets. "While my brother worked at the forge, I found work some days driving a wagon and others mining. Actually I was working like a dog and had nothing to show for it. When, seeing that all my efforts were gaining very lIttle, I abandoned the mines and my teams and in partnership with my brother, we became merchants. My brother had become quite skilled as a blacksmith and had a ready-made clientele among the miners. As for me, I could sell all kinds of merchandise.

"Our house was soon well stocked. Customers began flocking from everywhere because I maintained honest prices and sold as low as possible. The success of the Pechauds attracted more than customers."

1854 April - their store was burgled and about $700 in gold dust and coin was stolen. The thieves were apprehended at Captain Raspail's boardinghouse on the corner of Broadway and State streets. $648 of the Pechauds' money was recovered. Unable to post bail in the amount of $4,000, the two men, Day and Brown, were transferred to the county jail in Sonora. (Columbia Gazette, April 22, 1854. p. 2 C. 1.)

1854 July 10 - "Soon we were reaping great profits and already contemplating our return to France, when one night, one terrible night, in the month of June (sic)1854 all that we had was lost. A fire erupted, and in the space of a few hours, the town, which was built of wood was just a pile of ashes.

(Actually the fire is said to have broken out the morning of July 10, 1854.

Somehow, the Columbia Gazette came out the next day with an edition detailing the damage.

"Feeling only rage, my brother and I went back to work to recover from the disaster and repair our fortune. Having learned a lesson, we dug a deep cellar, and over this cellar we raised a new building, made entirely of brick, with iron doors, window frames and shutters. Not a single stick of wood was used in its construction.

Our little town was quickly rebuilt even more beautiful and secure than before. In a short time we

recouped our losses and were convinced that from then on we would be safe from any future conflagratIon.."

1857 August 25th - "A new fire erupted in a Chinese dwelling opposite our own. The fire started on the north side of Jackson Street." The Pechauds lived on the south side, approximately where the State Park office is now (was before 2010) located. "We only had time to seal all our doors, windows and shutters

and to abandon our dwelling to the grace of God."

1857 August - "Like the time before, the whole town was leveled. Not a single building appeared to be left standing." (According to Herbert O. Lang's History of Tuolumne County, only the northern portion of the town burned. The Pechauds are not listed among those who suffered losses, however, those enduring minor losses were not noted.) "When we made our way back to our store, we found it standing in the midst of rubble and ashes. It had not burned, but because of the intense heat, the doors and shutters had buckled. Air currents had found their way inside and the fire was smouldering in the darkened interior."

Immediately we began to seal all the gaps at the risk of our very lives because our cellar contained

several hundred kilos of blasting powder. Needless to say, we were quite anxious about it! Fortunately, we

managed to douse the flames."

Again, according to Lang, others who had stored powder were not so lucky. The gunpowder in the store of H. N. Brown exploded and resulted in five deaths (actually 6) and numerous injuries. In the aftermath of this fire, brick was no longer viewed by Columbians as the great protection from total ruin.