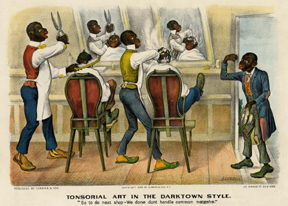

THE BLACK BARBER.

(AKA: Tonsorial Artist.)

1820 - 1890

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard.

These 1840's razors were the tool of trade.

San Francisco was home to sixteen black-owned barber shops as early as 1854, and during the 1860s, a former slave named Peter Briggs enjoyed a monopoly as the sole barber in Los Angeles. From their success at capturing the high-end of the market, black barbers amassed considerable wealth. One out of every eight African Americans in the Upper South worth at least $2000 in 1860, the standard for affluence at that time, owned a barber shop. Northern black barbers enjoyed prosperity as well, most notably by becoming the wealthiest African American residents in Cleveland, Ohio and New Haven, Rhode Island. They flourished, moreover, in spite of growing competition from European immigrants and deteriorating race relations that called into question how natural it was for African Americans to work in barber shops. In a feat unparalleled in the history of African American business, black barbers competed against white barbers for white customers, and they won. To understand how they met these challenges requires examining the tradition of enterprise that they created.

Black barbers fended off white competitors by preserving the artisan system, inventing first-class barber shops, and catering to the racial stereotypes of their white customers. Of these elements, the artisan system formed the cornerstone of the black barbers' tradition of enterprise. It ensured work and decent prices for all through a system that took care of barbers from the moment they entered the trade until their death. Graduating through a series of reciprocal relationships, barbers started out as apprentices living under the roof and supervision of a master barber until they were eighteen or twenty-one. The frequency with which black barber shop owners took apprentices and the care they provided for their wards exhibited a commitment to mutuality. In exchange, the elder barbers not only secured inexpensive help in their shops, but they also maintained high levels of skill and limited competition by controlling entry to the trade. Barber shop owners looked out for journeymen barbers as well, taking them into their homes, allowing them to court their daughters, and helping them become barber shop owners. These bonds of mutuality grew out of the African American community, with relatives, neighbors, and fellow church members of barbers arranging to have their son become an apprentice. Held together by such mutual care and respect, the fraternity of black barbers functioned like a medieval guild that established a virtual monopoly over the upscale end of the trade. Of course they would have had nothing to defend if they failed to attract upscale customers.

By combining elements of a luxury hotel, a spa, and a clubhouse in one business, black barbers invented the "first-class" barber shop. Their penchant for entrepreneurial innovation placed them in the forefront of the growing number of businesses such as hotels and photographer's studios that installed commercial parlors, luxurious accommodations for the public outfitted after the latest fashion. Commercial parlors featured the items that later became the hallmarks of Victorian home décor: carpets, window draperies with lace, matched sets of upholstered furniture, "fancy" chairs, a center table, a piano, a decorated mantel, and smaller objects such as framed pictures. As a result, experiencing luxury became part of the service that customers bought. Black barbers gave their customers further incentive to linger by offering hot baths and a range of goods from perfumed soap to cigars and suspenders. They also created an air of exclusivity by mounting shaving boxes in which regular customers could store their own personal shaving mug. Typically, men would buy mugs stamped with their initials in gold letters or an emblem representing their profession. These innovations had the effect of transforming the mundane act of getting a shave and a hair-cut into a glamorous ritual associated with consumption and status. Yet, since white barbers could also open first-class establishments, black barbers took their one unique characteristic - their race - and made it into a business asset.

Along with the skills they possessed as artisans and entrepreneurs, black barbers needed the talents of an actor so they could play the role desired by their white customers. A perceptive understanding of white men informed their performances. W.E.B. Du Bois defines this insight with his concept of double-consciousness, which he described as a sense "of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity." Because they understood how whites saw them, they were able to create masks that white customers found appealing.

Herman Melville demonstrated how successfully barbers donned masks in a passage from the novella Benito Cereno where he has a character named Captain Delano remark, "there is something in the Negro, which, in a particular way, fits him for avocations about one's person. Most Negroes are natural valets and hairdressers." Due to the inferiority of African Americans, he continued, it was natural for them to serve whites, and their skill reflected a devotion to their superiors. It was an expression, he asserted, of "that susceptibility of blind attachment sometimes inhering in indisputable inferiors." For black barbers, such beliefs guaranteed lifetime tenure in their jobs, so they worked within the existing structure of race relations while they awaited a better day.

For more see the whole at: Regional Identity, Black Barbers and the African American Tradition of Entrepreneurialism. from the The Southern Quarterly; A Journal of the Arts in the South.

www.albion.edu/library

Derrogatory drawing of black barbers.

This page is created for the benefit of the public by

Floyd D. P. Øydegaard.