BLACK STEVE

Information on a personality.

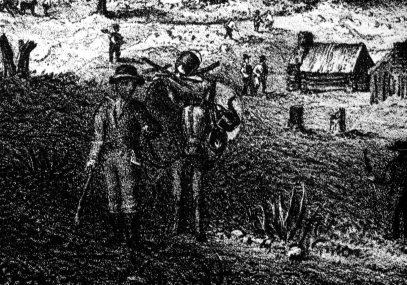

Drawing of 1852 wood cabins at Maine Gulch, Columbia's winter-made "river"

where todays south parking lot is currently.

STEPHEN SPENCER HILL

(The following account follows John Jolly's diary)

A Brief History of Stephen Spencer Hill

Fugitive from Labor by Carlo M. De Ferrari